A frequent question in our support group and in our monthly virtual “meet-ups” surrounds the need to know how severe respiratory involvement in Neuromuscular Disease (NMD) will get. It’s a question asked more often by those diagnosed with NMD later in life and/or the newly diagnosed. Sometimes the question comes from a parent of a child who has an NMD. Understandably, they want to know if bi-level mechanical ventilation will eventually be needed all day to support breathing. Sometimes they also want to know how long their breathing may be adequately supported. It is wise to want to plan ahead with any chronic medical condition. Questions surrounding respiratory involvement are just one example of why having a genetic diagnosis to confirm one’s exact form of NMD or disease subtype can be helpful. If the diagnosis is Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS), many scholarly articles reference the rate at which respiratory muscles are expected to decline and the degree of severity of weakness. Even for long-studied NMD diagnoses such as Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy (DMD) and Spinal Muscular Atrophy (SMA) Type 1, a lot of research has been published to advise of expectations for respiratory decline. For those with more slowly progressive and lesser studied NMDs, it may be impossible to know what to expect in terms of how weak the respiratory muscles will get and ultimately how much breathing support one living with that diagnosis might need. If you know your specific diagnosis, you may gain clarity about the rate of respiratory/breathing muscle decline and potential severity by reading papers published from natural history studies about your specific NMD type or disease subtype. For example, if you live with Limb Girdle subtype R1/2A, search an internet browser for “natural history limb girdle 2A.” If you struggle to find published papers on natural history, NMD-related nonprofit organizations (i.e. Cure CMD, Cure SMA, Parent Project Muscular Dystrophy, etc.) that raise funds to research treatments and/or cures for your specific condition may be able to assist you in obtaining published papers about the natural history of your disease. You may even find these publications on your own on the nonprofit organization's website. Some natural history studies include details like the average age to begin assisted/mechanical ventilation with that diagnosis and even the rate of annual decline of Forced Vital Capacity (FVC), a measure that is taken during Pulmonary Function Testing (PFT) that shows the total amount of air forcibly blown out after taking your deepest breath. Any published details are based on the study participants and may or may not reflect all individuals with that diagnosis. Physical changes to one’s body through skeletal abnormalities like scoliosis and kyphosis can amplify the degree of respiratory muscle weakness one may have. Other influencing factors can be retained airway secretions (mucus), micro atelectasis (the collapse of an area within the lung), and repeated respiratory infections that escalate to pneumonia. Some with the same diagnosis, including siblings, can have differences in their clinical presentation, which can mean one has more pronounced respiratory muscle weakness than the other. With all of these factors to consider, questions about respiratory/breathing muscle decline and severity are difficult to answer with 100% certainty.  Many of us with congenital forms of NMD have lived decades with uncertainty about various aspects of our diseases, including the rate of respiratory decline. Some have had clinicians make educated guesses and have been proven wrong. As research for the NMDs continues at an exciting pace and more patients get involved to participate in studies, one can only hope that more details about the rate and potential degree of respiratory decline will become known and shared within the individual disease communities. Uncertainty can be scary and frustrating, but one thing is certain: support is available! Join and participate in meaningful discussions in support groups for those with the same form or subtype of NMD. Facebook has dozens of these groups; you just need to search for and find the one that's for you. And if a support group does not exist for your form of NMD or subtype, create one! Then post a link to it in other general NMD groups where individuals with that disease may be members, helping to recruit them to join and participate in your group. The Breathe with MD Support Group offers peer support specific to breathing muscle weakness in NMD. There are members who have used both noninvasive and invasive forms of mechanical ventilation for more than 25 and 30 years respectively. The feedback and insight from members can be extremely valuable, not to mention the feeling of camaraderie one can receive by communicating with individuals going through the same challenging journey. Wishing you all the best, Andrea Dear Andrea, How do I know when it's time to start daytime mouthpiece ventilation? I really don't want to do this unless it's necessary. Sincerely, Reluctant to Start MPV  Dear "Reluctant to Start MPV," Looking back, I had mixed feelings about using Mouthpiece Ventilation (MPV). I feared it would make me look weaker than I was. I was concerned about my appearance and did not want mouthpiece ventilation to be socially "off-putting." At the same time, I knew it would be less extreme for me than wearing my nasal mask in public, and I was not going to deprive myself of something I needed just because I was concerned about my appearance. In the spring of 2015, I asked my neuromuscular pulmonary specialist to try mouthpiece ventilation, because I wasn't sure if switching to a multi-mode ventilator and using a new mode of noninvasive ventilation for sleep was going to be enough to make me feel back to "my normal" during the day. I had been fighting sleepiness throughout the day, nodding off briefly if sitting quietly and reading and even found myself struggling to stay alert in meetings. I would come home from work so worn out that going to bed was all that I could do, and it took a multi-hour nap on my ventilation to replenish my energy. In July of 2015, insurance approved my switch from a bi-level device that used a BiPAP S/T mode to a Trilogy 100 multi-mode, dual-prescription ventilator. I was labeled "failing BiPAP" after trying BiPAP S/T settings increases numerous times over a period of months. I had reached the max pressure on the machine and still experienced symptoms that I was having before I began to use mechanical ventilation. The Trilogy was delivered and enabled with one prescription for sleep (AVAPS AE) and a second setting enabled for use with a mouthpiece, as needed. To my disappointment, the settings were wrong; I was given the same settings for use with a mouthpiece as I was prescribed for nighttime mask use, minus some subtle differences. I knew the second I placed the 22 mm mouthpiece in my mouth that it was wrong. I was getting several different-sized breaths and was unable to stack breaths (sip small breaths in succession to fully fill my lungs as if I was taking a deep breath). Also, the mouthpiece was blowing air on me forcefully when I removed it from my mouth. This went against everything I knew about mouthpiece ventilation from others who were using it; this was so discouraging! Both my neuromuscular specializing pulmonologist (now retired) and respiratory therapist (RT) at the time had never prescribed or worked with a patient using mouthpiece ventilation. This is common in the US. I got the impression that it was going to be up to me to sort this out. I knew the mode enabled was incorrect, and another individual with the same neuromuscular diagnosis assisted me in understanding what settings mode I needed, based on what he was using. It was the Trilogy 100's proprietary volume-based mode called "Mouthpiece Ventilation (MPV)." And to prevent the constant, strong flow of air, a setting referred to as a "kiss trigger" would be enabled. My RT contacted a regional Respironics representative who agreed with what I had learned. My pulmonologist signed off on the change, and the new settings were enabled. As a result, the device only delivered a breath when I closed my lips around the mouthpiece, delivered the same sized breath each time, allowed me to stack small breaths in succession, and only blew a light amount of air when the mouthpiece was outside of my mouth. After a period of using MPV almost daily for a few years, I found I no longer needed it except in specific scenarios:

But back to the question you asked, "When do I know it's time to start mouthpiece ventilation?" When to start MPV can vary from person to person. In some cases, the person wakes up, goes off of their nighttime ventilation, and feels as if they need ventilation again within minutes to a few hours. For others, they feel the need to have breathing support periodically throughout the day. In some cases, individuals are able to work with their clinician(s) to adjust their nighttime ventilation, increasing pressure and/or tidal volume, lowering EPAP (expiratory positive airway pressure), changing respiratory rate, or even moving from a BiPAP S/T mode to an AVAPS AE or other mode. When changes are made in nighttime mechanical ventilation, some find they do not need mouthpiece ventilation during the day. The bottom line: you should not shy away from asking to try mouthpiece ventilation. If you do not try it, you will never know if it will work for you. What do I need?

Additional Considerations: If you are unable to lift the mouthpiece to your lips, you may want to consider a gooseneck tubing assembly that places the circuit within wheelchair-mounted bendable tubing that allows the user to move their head slightly to reach the mouthpiece and close their lips on it. You may also need a transport bag for your vent and/or backpack hooks on the power chair to safely transport it. Your respiratory care company should be able to assist in ordering one of these or suggest a store-bought alternative. Some have requested a vent shelf to be added to the back of their power chair, a part your wheelchair provider should be able to assist in finding. Be sure to get all of the specifications for this before ordering, as some find a shelf makes the vent stick out further than they want. Individuals that are still ambulatory may want to consider pushing the vent on a pole that can be purchased for their specific model or placing it on a rollator walker that has a seat. Using a small cart on wheels is also an option some have used. You may need assistance moving the same vent from the wheelchair to the bedside and vice versa; the portable vents of today weigh approximately 8-10 pounds. Many United States insurance companies will not cover a second vent, so this daily task is often assigned to a caregiver.

I hope what I have shared helped you to learn more about mouthpiece ventilation so that you can speak to your clinician and determine if it might be right for you. Take care, Andrea Dear Andrea, I have Muscular Dystrophy related breathing issues, and my doctor isn't sure what to call them. He mentioned maybe it's COPD, or maybe it's something milder like asthma. Does this sound right to you? Sincerely, Unsure of Diagnosis Dear "Unsure of Diagnosis,"

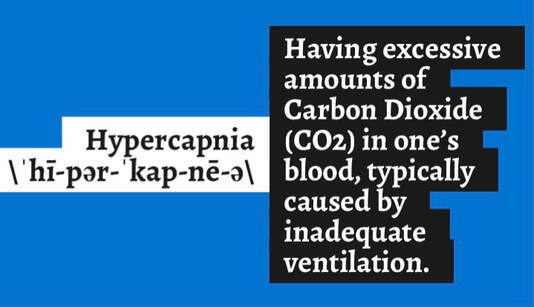

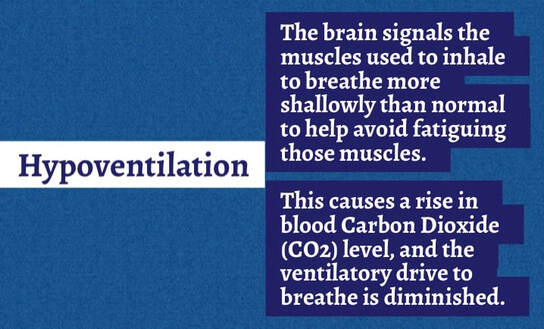

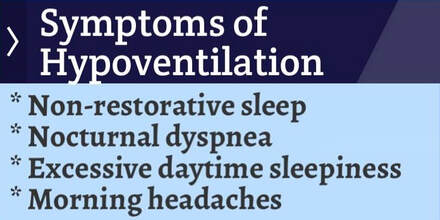

You are not alone. I personally spent more than a decade of my life thinking I had severe asthma. I was reporting a tightness in my chest which made it tough to breathe and was prescribed an ever-increasing dosage of a daily asthma "maintenance inhaler" that my weakened breathing muscles were too weak to inhale deeply into my lungs, even with a spacer device. This was all the result of seeing a pulmonary critical care specialist who was not experienced in treating Neuromuscular breathing weakness but was an expert in COPD and asthma. Looking back on this, I feel stupid, but it's hard to know what you don't know. It wasn't until after my middle sister Cheryl died from inappropriate care for Muscular Dystrophy related respiratory failure that I read a lot of medical literature about ventilatory pump failure, mechanical ventilation use in Neuromuscular Disease (NMD), and books authored by Dr. John. R. Bach. A Neuromuscular pulmonary specialist at a university-based hospital confirmed I did not have asthma when she reviewed my medical records, including sleep study results, and ordered her own pulmonary function testing (PFT). I instead had a weakened diaphragm, weakened and contracted muscles and joints between my ribs, and was living with chronic hypoventilation (under ventilation) that had begun showing itself in the form of sleep-disordered breathing. All of it stemmed from my NMD and had absolutely nothing to do with asthma. In fact, once I got prescribed the correct interventions (bi-level mechanical ventilation and mechanical insufflation/exsufflation (aka mechanical cough asssitance), the chest tightness I had left along with the ever-worsening fatigue, daytime sleepiness, and morning headaches. An inaccurate diagnosis like mine is not uncommon, as I have met many others with NMD over the years who have similar stories. With COPD, individuals will have difficulty exhaling all of the air from their lungs. Because of damage to the lungs or narrowing of the airways inside the lungs (obstruction), exhaled air comes out more slowly than normal. At the end of a full exhalation, an abnormally high amount of air may still linger in the lungs. Contrast that to those of us with NMD. We are generally free of lung issues and oftentimes exhale air in one fast push. Instead, our issue is with the muscles that allow us to ventilate our lungs by moving air into and out of them. In NMD, we have a restrictive, not obstructive pattern of breathing, meaning we have the inability to take large, deep breaths. This restriction can be caused by weakened breathing muscles alone or may be amplified by a skeletal defect, more commonly seen in congenital forms of NMD, that leads to an abnormal curvature of the spine such as scoliosis. Others may have a spinal curvature known as kyphosis or even spinal rigidity, all limiting the ability of the rib cage to develop normally and/or expand fully, ultimately affecting breathing. Some of us also have contractures and tightness in the muscles and joints between our ribs. All of this can limit our ability to take large, deep breaths, even more so when we are supine (lying down) and our natural ability to breathe deeply is reduced. In conditions like asthma and COPD, airway obstructions, they are treated very differently than that of the restrictive pattern of breathing seen in NMD. This is the main reason why I recommend that you work to find a specialist in neuromuscular breathing weakness who can do a thorough evaluation and testing and then interpret that based on an eye experienced in detecting and interpreting neuromuscular breathing weakness. Unfortunately, these specialists can be difficult to find in the United States (US), and more so in rural areas. For that reason, many of us have to drive or even fly hours from home to get the necessary medical care. A telehealth visit may be an option for you, at least for an initial consultation. It is ultimately your choice if you stay with a clinician who is not trained or experienced in treating those with neuromuscular breathing weakness. But doing so can lead to poor outcomes and reduced quality of life. Some in the NMD community have been able to self-advocate (speak up for themself) to help educate the untrained clinician about neuromuscular breathing weakness. All people and clinicians are different, so it's impossible to know if your particular uninformed clinician relationship is salvageable or if a second opinion referral to a neuromuscular specialist is the better route to take. If you have not already done so, please read my post "Sleep Study Results: A Unique Case," as it will alert you to another challenge many of us have when new to the breathing muscle weakness journey, an inaccurate sleep study interpretation and subsequent inappropriate interventions prescribed. Wishing you the best, Andrea  I think everyone in the United States has heard the term, “being frank.” I am "being frank" because I care about those living with Neuromuscular Disease (NMD) and want to help them prevent a respiratory crisis, something my family experienced in the lead-up to my middle sister Cheryl's death. While I am not a medical professional, I am on the receiving end of all e-mails and social media private/direct messages for Breathe with MD, Inc. I have also received dozens of messages to my own private accounts over the years from individuals living with an NMD who are seeking advice about breathing concerns. Nearly all of these communications have commonalities. One of those is the reluctance of adults with an NMD to prioritize pulmonary care, and it seems to be worse among those with slowly progressive forms of NMD, those that were diagnosed later in life, and those that are extremely busy making a difference in life. There are many reasons why an individual might not prioritize something so serious as their breathing. Sometimes a past medical trauma makes individuals with an NMD fearful or distrustful of medical professionals and their recommendations. Some are simply sick of going to medical appointments and do not believe they can handle another doctor or type of care. Others are fearful of the equipment such as insufflation/exsufflation/mechanically assisted cough (MAC), commonly marketed as Respironics CoughAssist and/or mechanical ventilation due to their lack of understanding or a pre-conceived, incorrect notion. Some wrongfully believe that starting these interventions will make them more dependent upon them over time or become worse simply because they used the respiratory device. Others believe they are so near death that the prescribed interventions will diminish the quality of their remaining life. Still, others have seemingly impossible barriers to accessing a clinician that can provide what is needed where they reside. This deeply saddens me because those of us who have made pulmonary care and interventions for breathing muscle weakness a priority have found that even if the initiation of these devices was a huge challenge, once we got through the adjustment phase, these devices improved our quality of life. Many of us wish we had begun use of the equipment years earlier and regret the delay to start. I personally know individuals with an NMD who have been using mechanical ventilation for 20-30 years, noninvasively with up to 24/7 continuous ventilation via mask and mouthpiece interfaces and invasively with a tracheostomy tube. Needing to start mechanical ventilation is NOT an indication that one's life is near the end, if they are living with an NMD. I can share countless stories to inform you of individuals with an NMD who did not use mechanical ventilation or even get a pulmonary evaluation who suffered from a reduced quality of life or even died. One individual that comes to mind was not using prescribed mechanical ventilation and died in their sleep due to months of unresolved and ever-increasing carbon dioxide (CO2) retention and its escalation to CO2 narcosis and then coma. Another became ill from a cold that quickly progressed to a chest infection, then pneumonia, and was hospitalized, intubated, failed numerous attempts for extubation to noninvasive ventilation and MAC, and nearly died during the ordeal. It took knowledgeable family members advocating and preventing the use of contraindicated interventions (i.e CPAP and unventilated supplemental oxygen). Thankfully, this individual lived to share their story. Still another individual with an NMD had a fall that resulted in a broken bone requiring orthopedic surgery. Their recovery nearly caused their death due to a lack of mechanical ventilation and pain medications suppressing their already reduced ventilatory drive, worsening their NMD-related hypoventilation (under breathing). Getting started on mechanical ventilation can be a challenge when healthy, so waiting until one is recovering from a medical procedure isn't the best or easiest time to do this. All of these individuals and/or their families that I have shared about would tell you NOT to do as they did and to make pulmonary care and the appropriate interventions a priority to prevent poor outcomes. Over the years I have come to know adults that are avoiding the tried and true interventions for breathing muscle weakness and are using what I will refer to as "alternative forms of care." These are attractive because they may be more convenient and/or clinicians that are unfamiliar with breathing muscle weakness and the appropriate interventions are prescribing or supporting the use of them. One common alternative is inhaling nebulized medications that are said to open up airways and help with breathing. There is no research to support use of nebulized medications only for weakened breathing muscles, as nebulized medications are not a substitute for mechanical ventilation and are used for obstructive airway conditions (i.e. asthma and COPD) or during illnesses such as a bronchial infection. Breathing muscle weakness is a restrictive condition and is treated differently. Another "wishful thinking" alternative is muscle training devices whose marketing claims to strengthen breathing muscles. While these devices may provide limited help in stretching weakened and/or contracted breathing muscles, they cannot bring back lost muscle strength that has left as a result of neuromuscular breathing weakness. The bottom line is that these alternatives don't assist us in ventilating (moving air into and out of) our lungs during sleep, and that is what we need help with when a Neuromuscular Disease has led to hypoventilation and/or hypercapnia. In contrast, some of the inter-related benefits of using mechanical ventilation when one needs it are:

Some of the benefits of using insufflation/exsufflation/mechanically assisted cough (MAC) i.e. CoughAssist are:

Please know that the organization I founded, Breathe with MD, Inc., is here to support you through its mission and programs. The Breathe with MD Support Group on Facebook has over 1,700 members, and the respiratory peer mentoring program for adults living with an NMD are excellent ways to get support to make pulmonary health a priority. Many are struggling to accept the gravity of respiratory muscle weakness, but your peers get it and will have suggestions for you. Do NOT give up; you are NOT alone; there are solutions to every challenge you may be experiencing or think you will experience! Wishing you all of the best, Andrea Dear Andrea, My sleep study results are in, and my doctor says I'm a unique case. He says I don't have any signs of Muscular Dystrophy related sleep issues, that I just have sleep apnea. For that reason, he's prescribing a CPAP. Didn't I read CPAP is not recommended? If so, now what?! Sincerely, CPAP Ordered Dear "CPAP Ordered," Your sleep study experience is SO common. But how could so many be a "unique case" and "just have sleep apnea?!" The truth is, when we see a specialist who does not specialize in neuromuscular breathing weakness or the clinician does not have experience interpreting sleep studies of individuals living with neuromuscular conditions, inappropriate equipment can be prescribed. In some cases, nothing is prescribed, because we are not "bad enough," according to their interpretation of our results. So many of us have been through this, so you are not alone! Another common problem is the sleep study did not include monitoring for both oxygen saturation and exhaled Carbon Dioxide (end tidal CO2). Lacking the "full picture" of our sleep can lead to supplemental oxygen being ordered, a more dangerous example of mismanagement. (You can learn more about the danger of unventilated supplemental oxygen for those with neuromuscular breathing weakness at https://breathewithmd.org/oxygen-caution.html.) What your doctor is ordering, CPAP, is not advised for those with weakened breathing muscles, because it offers one continuous positive airway pressure that blows while you’re inhaling and exhaling. It can be difficult or exhausting to exhale against that pressure and make us feel worse. For more about this, consider watching my video “BiPAP or Bi-level Versus CPAP: Understanding Why CPAP is NOT for Neuromuscular Disease,” at https://youtu.be/A1gH6hfZigo. The point of assisted ventilation at night is to rest the breathing muscles by assisting with the process of moving air into and out of the lungs, either reducing the effort or completely eliminating that effort. Only bi-level devices (often referred to as “bipap,” and portable ventilators) move air into and out of the lungs by offering two different positive airway pressures, one for inhaling (IPAP), and a second much more reduced pressure for exhaling against, (EPAP). In some cases, with ventilators using what's called "active circuit," EPAP is set to zero, eliminating all effort to exhale. It can be difficult to confront a clinician who is not familiar with neuromuscular breathing weakness and is incorrectly prescribing CPAP. Trust me, I've been there; 2013 was my "lucky year" for that! This clinician may even be known as an expert in your area and has prescribed CPAP hundreds if not thousands of times for individuals with central and obstructive sleep apneas. You may feel intimidated challenging his or her opinion. While it is not impossible for an individual with a neuromuscular condition to have central or obstructive sleep apnea, it’s more likely that the sleep study equipment is interpreting the weak, shallow breathing and hypoventilation (under ventilation) as lack of breathing or “apnea.” It takes someone with a trained eye to realize what they are seeing is instead lack of muscle effort caused by the neuromuscular condition. If you are looking for documentation to share with your clinician in the effort of self-advocating to get the appropriate care, you might want to share an article published in the MDA Quest magazine called, “Not Enough ZZZzzzs.” It’s available at https://www.mda.org/quest/article/not-enough-zzzzzzs. Another easy-to-follow document is Muscular Dystrophy Canada’s, “Guide to Respiratory Care for Neuromuscular Disorders” available at https://muscle.ca/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/RC13guide-EN.pdf. You can find Chapter 7: Noninvasive Ventilation on page 25. If after sharing materials and discussing this with your clinician, he or she is still insisting you need CPAP (as mine was), you have the right to request a second opinion referral to another clinician that YOU select. A neuromuscular pulmonary specialist, usually located at a university-based hospital, is your best bet for getting an accurate assessment and plan of care for your breathing weakness. You may feel like this will offend or disappoint your current clinician and cause conflict. Understand that clinicians are used to this and understand that patients sometimes need another opinion. And when it comes to issues with our breathing, I am not exaggerating when I say that your life could depend on the decision to see a different clinician. Appropriate care can make a tremendous impact on your health and quality of life! I have seen this so many times in the individuals I've met through Breathe with MD, Inc.

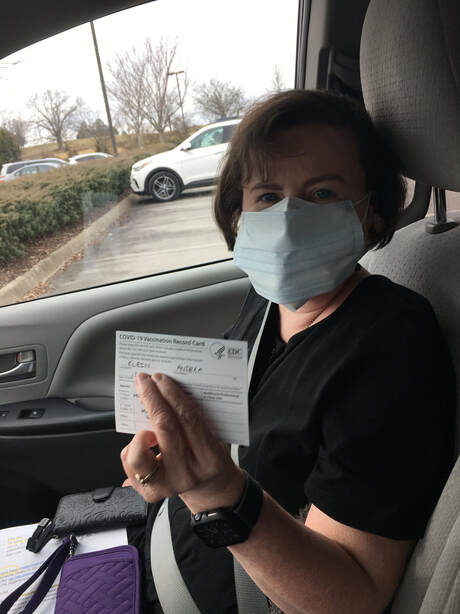

Having said all of that, I hope my response to your question has been helpful and that the resources I shared provide the additional details you need to assist you in getting the care that’s right for you. Best Wishes, Andrea  Dear Andrea, I heard you got the second dose of the COVID-19 vaccination and you had some side effects. What happened? Sincerely, Individual Living with NMD Dear Individual Living with NMD, Dose 2 of the Pfizer and Moderna vaccinations both have a reputation for causing side effects, even for those who had no side effects from the first dose. "The most common side effects are injection site pain, fatigue, headache, muscle pain, and joint pain. Some people in the clinical trials have reported fever. Side effects are more common after the second dose; younger adults, who have more robust immune systems, reported more side effects than older adults." Reference: https://www.statnews.com/2021/02/02/comparing-the-covid-19-vaccines-developed-by-pfizer-moderna-and-johnson-johnson/ I personally know some with neuromuscular conditions who had nothing more than injection site soreness after dose 2, but I also know those who had fatigue and muscle aches. I "prepared for the worst" but was not expecting the symptoms to shift direction and begin so many hours after vaccination. That caught me off guard. My Dose 2 of the Pfizer vaccine was during another late Thursday afternoon appointment. The shot was fast and painless. We went straight home after my 15 minute waiting period. Within minutes, my arm was already sore, a faster development of soreness than I had experienced with the first dose. I awakened earlier than usual that morning, so I was more than ready for a nap when we got home. I got into bed and used my assisted ventilation to relax and watch TV. Within an hour, a slight headache began. I slept for about two hours. While eating our carryout supper an hour later, I began to feel as if I had not even napped. I was very fatigued. It was the kind of fatigue that made eating and holding one's head up a lot of effort. I wasted no time and got ready to return to bed. I took ibuprofen because that mild headache was getting more noticeable. I had a rough night and experienced what I will call "temperature regulation issues." One minute I was hot, the next I was cold, and then soon after I was hot again. The heat was a strange sensation that didn't seem like a hot flash. It radiated over most of my body, just under the surface of my skin. This symptom went on for hours and made it difficult to get comfortable. Throughout the night, I woke up a couple of times feeling hungry enough to eat a large meal, but I stayed in bed.  The Day After I got what I am guessing was five hours of sleep, and when I signed on for work the next morning, I was quite tired. It was hard to tell if that was from lack of sleep or the vaccination causing fatigue. During my lunch break, I was feeling less tired, but within minutes of deciding I would work my full shift, I began to feel those "temperature regulation issues" starting again. At this point, it had been about 20 hours since my vaccination. Chills were more pronounced and got increasingly worse over the next two hours along with new joint and muscle aches. That strange heat sensation under the surface of my skin was back too, and it was worse. By the time my work day ended, I was bundled up in jackets and blankets and feeling miserable. It took everything I had to focus and get through the last hour of my work day. I checked my body temperature to find it was only slightly elevated above my usual temperature and not high enough to be considered a fever. I took more ibuprofen, went straight to bed, and I slept on my assisted ventilation for nearly four hours. The Night After At 30 hours post vaccination, I was a whiney, achey mess and had not improved much. The aches were from the soles of my feet to the top of my scalp. Thankfully it was not a constant ache, and I would alternate from aching in one body part to aching in another. At times, it felt like my wrists and ankles were broken. If ibuprofen was helping the pain, I don't know how I would have felt without taking it. Ibuprofen perhaps kept my body temperature from never exceeding 99.9 degrees Fahrenheit, however. Slowly the muscle and joint aches eased off. The one symptom that remained constant was that hard to describe sensation that felt like my blood or tissues were hot under the surface of my skin.  I got up briefly around midnight and discovered my arm was more sore than it had been and had a swollen red mark at the vaccination site. My entire arm was slightly pink and itching. I applied an over-the-counter hydrocortisone cream that helped. While up, I felt like I was finally starting to feel less achey. I began to have hope that this was going to pass the next day. Day Two I slept very soundly for eight hours, unlike the night of the vaccination. I woke up to discover the arm that had been vaccinated felt different, almost like I couldn't fully hold it against the side of my body, like there was something obstructing it. When I got up and looked closer, I could see my armpit and the areas surrounding it were swollen, and it was really sore. After a few minutes of reading online, I realized this was likely a swollen lymph node in my armpit, something that can happen after any vaccination and is a normal immune system response. It's a documented side effect of both the Pfizer and Moderna vaccinations (for either dose 1 or 2) and has been in the news. Within a couple of hours of getting up (now 45 hours post vaccination), I felt mostly back to normal, other than the slightly itchy and sore arm and armpit. Over the next two days, at times I felt a bit sluggish, almost as if the vaccine fatigue is still somewhat there. This symptom had little to no impact on my activity though. You may be asking, "Was the second dose of the vaccine worth these annoying side effects?!" To that I resoundingly say, "Absolutely!" These side effects and the inconvenience were minor compared to contracting COVID-19 and risking a severe outcome. Tips In closing, my advice is to prepare yourself for a day or two of lying around or simply being less productive after dose 2. That might mean missing work or feeling unable to do certain activities of daily living. For me, it meant I could not prepare meals until the day after vaccination, nor did I feel capable of safely taking a shower independently. I also spent significantly more time lying in bed. My hope is that your experience is less annoying than mine and that you will quickly see what a blessing it is to get vaccinated and feel the sense of hope it gave me that life can slowly begin to return to some degree of normalcy and be more safe. I will continue to double-mask, socially distance, wash my hands thoroughly and frequently, but I will feel safe enough to go to necessary appointments and interact briefly with others from outside my home. I am ecstatic about being able to do some of the more mundane tasks of life again, once my immune system has had a couple of weeks to finish building immunity. Wishing you all the Best, Andrea |

AuthorAndrea is the Founder & President of Breathe with MD, Inc. and served as Ms. Wheelchair Tennessee 2017. Her blog posts are based on experience living with a Neuromuscular Disease. The blogs are not to be used as a substitute for medical care. Always seek medical advice and care from a licensed medical professional. Archives

June 2023

Categories |

Breathe with MD, Inc. is a U.S. registered 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization. Donations are tax deductible to the extent allowable by law.

Note: This website should not be used as a substitute for medical care. For medical care or advice, please seek the care of a clinician who specializes in the breathing issues of those with Neuromuscular Disease (NMD).

Web Hosting by Hostgator

Note: This website should not be used as a substitute for medical care. For medical care or advice, please seek the care of a clinician who specializes in the breathing issues of those with Neuromuscular Disease (NMD).

Web Hosting by Hostgator

RSS Feed

RSS Feed