In our first VentilatedVoices questionnaire, recipients of our Breathe with MD, Inc. monthly email update and our social media followers were asked, "What is the BEST thing about living with breathing muscle weakness in Neuromuscular Disease (NMD)?" and “What is the WORST thing about living with breathing muscle weakness in Neuromuscular Disease (NMD)?" We appreciate all who participated, especially those who agreed to allow us to share a portion or all of their feedback. Below are a few of the responses regarding the BEST thing about living with breathing muscle weakness in NMD, as stated by individuals living with an NMD and using mechanical ventilation. “I would say there is no 'best' thing.” - N.R., CA, USA “Essentially my lungs are not the problem and because of technology our mechanical ventilation can adequately compensate for our muscle weakness.” - V.G., GA, USA “Friendship & support made with others in same situation.” - G.M., Glasgow, Scotland “Makes me value the little things in life most take for granted.” - C.V., CA, USA “I've become more resilient.” - L.J., VA USA Below are a few of the responses regarding the WORST thing about living with breathing muscle weakness in NMD, as stated by individuals living with an NMD and using mechanical ventilation. “I don’t like that I have to rely on electricity to sleep or take a nap, and that external batteries are expensive, not covered by insurance, and they are heavy.” - N.R., CA, USA “Always on the edge of going to the hospital and not being able to actually do the things you want to do.” - J.A., VA, USA “It limits what I can do, because I get out of breath with exertion. So, it keeps me pretty much home bound most of the time.” - B.S., WA, USA

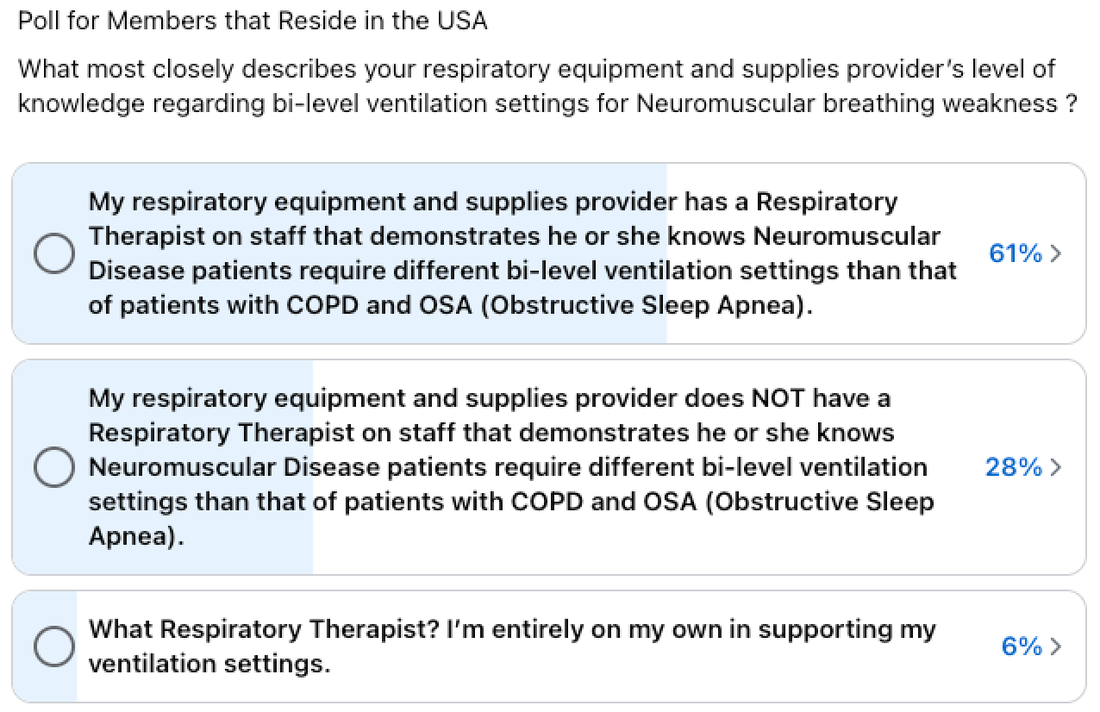

“The pain, exhaustion, fear. Both mentally and emotionally and physically.” - C.V., CA, USA “But that is a toss up to travel--to have to lug large pieces of equipment around onto a plane or from hotel to hotel is even worse---dealing with the travel personnel and difficulty of set up on small bedside tables makes a trip so much more difficult than it has to be.” - V.G., GA, USA VentilatedVoices is one way we help raise awareness about the opportunities and challenges for those using mechanical ventilation for Neuromuscular breathing weakness. Look for future VentilatedVoices questionnaires to share your experiences and feedback. By Andrea Klein Founder & President, Breathe with MD, Inc. "What happened next was unexpected, frightening, and infuriating."  As a user of noninvasive ventilation for nearly 10 years, I used the same brand and model portable ventilator for more than eight of those years. I never anticipated the type of challenges and degree of frustration that I would experience transitioning from that ventilator to one made by a different manufacturer. The process included surprises, delays, and finally…lessons learned. I’m summarizing seven of those here. 1. The prescriber (MD, NP, PA, etc.) can order the change from one ventilator to another at any time. I knew a change was coming because my ventilator had been recalled and was still not repaired. Additionally, my respiratory DME (durable medical equipment) provider ended their contracted maintenance for that brand of respiratory equipment. My Respiratory Therapist (RT) and I had formulated a plan for me to transition to another ventilator (vent) brand when my unit would need its 10,000-hour regular maintenance near the start of 2024. At my neuromuscular pulmonary appointment in June 2022, I was advised I would no longer see the MD but would move to the Nurse Practitioner (NP) for subsequent appointments, as long as I remained stable. I saw that NP in June 2023, and changing vents was not part of our discussion. One month later, I was notified via the patient portal that this NP had sent an order for me to get a new vent. 2. Existing ventilator settings could be forgotten or even “up for debate.” My respiratory DME originally received the order for a new vent, but it was missing the settings to be enabled for my two prescriptions, (AVAPS AE for sleep and mouthpiece ventilation, as needed for daytime use). The settings were needed before delivery could be scheduled, so I sent a patient portal message to request those in a revised order. What happened next was unexpected, frightening, and infuriating. I had been on a tidal volume, the amount of air that moves into and out of the lungs in a cycle, of 525 ml for AVAPS AE mode for the last 5-6 years, and the order for the new vent specified 350 ml. My RT believed this reduction could be harmful to me. I was diplomatic but firm in my next patient portal message, explaining to my MD that the NP had ordered this reduction in tidal volume and I would refuse to use the new vent, as it was lower than what was prescribed in 2015. Further, I explained my medical records with this same medical practice show I’ve been using 525 ml for more than 5 years. Within hours, I received a response that an error had been made (albeit not clear as to why) and the order would be corrected with my current tidal volume and re-faxed. Unfortunately, that is not what happened. Copies of the incorrect order continued to be sent to my respiratory care DME, or they received nothing after each confirmation that another order had been electronically faxed. Phone calls between my RT and the nurse and NP occurred, and I continued sending periodic messages via the patient portal. By the time the RT received the corrected order, weeks had passed, and more than 20 messages had been sent back and forth about this vent. My RT believed the individuals involved in preparing the order were unfamiliar with IVAPS (Intelligent Volume Assured Pressure Support), the type of noninvasive ventilation I was moving to on the new vent, the near equivalent of what I was using on my existing vent, AVAPS (Average Volume Assured Pressure Support). The only plausible explanation he could think of for their initial tidal volume reduction was based on their knowledge of what tidal volume a person my size would need while intubated (receiving ventilation through an endotracheal tube), not considering noninvasive ventilation at home with an intentional leak and thus a necessary higher tidal volume. Whatever the reason, in the beginning of the process, I felt as though I had to fight to defend what had been keeping me stable for so many years, but my next source of anxiety was trying the new vent. 3. Your RT may have little to no experience with Neuromuscular breathing weakness ventilator settings. My RT lacks experience with neuromuscular noninvasive vent settings but makes up for that with his lack of ego, desire to continue learning, and respect for patients who have knowledge about their respiratory health. For that, I’m grateful. He was at my home multiple times and had no problem leaving my existing ventilator for use as I was adjusting to the new one. Vent settings orders often include a range of values with some degree of leeway for the RT to adjust for comfort. On vent delivery day, I made the mistake of not reclining (and I know better!) while trying the vent and later realized what felt okay while seated was intolerable while lying down. The breath triggering, length of time for each breath, and cycling in and out of inspiratory and expiratory pressures on the new vent were completely different from my old vent. I had moments that night while awake in bed that felt like I was struggling to get enough air. What would have happened if I had gone to sleep?! Having my old vent was critical to getting me through that first night and while waiting a couple of days until my RT could return to make adjustments to the settings. We had agreed up front that I would keep the old ventilator for at least a couple of weeks during this transition. 4. It may not be possible to use the same settings on the new ventilator. My old ventilator’s proprietary AVAPS mode had fields that do not exist in the new vent's IVAPS mode and vice versa. The same can be said about each vent's mouthpiece ventilation mode. Each manufacturer names settings differently, and units of measure (seconds versus milliseconds, liters versus milliliters, etc.) may also be different. This made it impossible to use the same settings in this transition. My RT had to provide a template of sorts for the clinician to use in revising their order so that all appropriate aspects of the prescribed settings were included. Ultimately, he had to get on a couple of phone calls to review the various settings with my pulmonary NP's RN. 5. The new ventilator may feel different from your previous ventilator. On my old vent, I used a 4.0 l/min flow trigger sensitivity, but I require what is labeled as very high triggering on the new vent. I required a flow cycle sensitivity of 20% on the old but 30% for the cycle setting to feel comfortable on the new. It was surprising to me that two manufacturers would have vents that are so different. This is why so many adjustments needed to be made after the initial vent setup provided on delivery day. I asked members of the Breathe with MD Support Group whether or not they had tried to transition from one manufacturer’s ventilator (used noninvasively or invasively) and had been unable to successfully do so. (This was during a time when I questioned if I would be able to successfully use the new vent.) I learned that no two vents, not even of the same model feel the same. One group member shared, “…even when my Trilogy vents get switched out for newer Trilogy (ie, when I reach the maximum blower hours), it still takes a day or two to adjust. Every vent is different even if it’s the same model. At least, that’s been my experience.” She continued, “If you think practically, it’s a machine and it’s virtually impossible for them to be identical. Unless I’m having major issues with a switch out, I give my body a few days to adjust to the new vent before I make any adjustments.” Another group member shared, “You'd expect two machines bought on the same day to perform the same but if not, one has more/less wear on seals, rings, and other parts to change pressures slightly.” 6. Multiple adjustments may need to be made to the new vent's settings. On his second visit, my RT got the new vent settings to feel closer to that of my old vent. It was tolerable for an entire night of sleep, but I was waking up due to an odd cycling difference. My RT has known me for several years and agreed that I could continue to try various minor setting changes on my own, something I was comfortable with and knew how to do. He had recommendations for things I could try, and I made note of them. 7. It takes time to adjust to the changes. After trying the new vent before having the updated and more tolerable settings, the muscles between my ribs felt a little sore each morning for the first few hours of the day. The longer I used the new vent, the more I realized it required more humidification than the old one to keep me from waking up with a very dry mouth. I had to try various temperature increases to finally arrive at the decision that an increase of 1.5-2 points was necessary. By the time I worked that out, the dryness triggered over-production of mucus (something I experience if I sleep without the humidifier on by accident), and I dealt with excess secretions for three to four days during my mechanical cough assistance therapy. I spent time reading about each setting on both the old and new vents to better understand them. This allowed me to more confidently make changes to the settings and arrive at comfort-type settings that made the new vent feel much closer in breath delivery to the old vent. It was an amazing feeling to achieve that, but I had to ensure my RT agreed with the changes. Thankfully, he was in agreement! If I had not made those changes on my own, the number of visits from my RT would have increased as would the duration of my sleep deprivation. And working, volunteering, and living with a Neuromuscular Disease (NMD) make lack of quality sleep extremely difficult for me. I had taken a full week off work for this vent transition, but delays in receiving the vent sadly meant most of those days were wasted. NMD Patients Changing Their Own Vent Settings? Now that I've shared those lessons, you may be wondering how common (or not) it is for an NMD patient to change their own vent settings. In the US, this happens more often than prescribing clinicians likely realize. I posted a poll in the Breathe with MD Support Group, and the responses give you an idea of how many are lacking needed NMD settings-knowledgeable RTs to support ventilator use and transitions like mine. I believe we have a problem that is rooted in a lack of NMD-specific curriculum content for RTs in training. Our being a minority in their caseload full of COPD (Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease) and OSA (Obstructive Sleep Apnea) patients who are nothing like us only amplifies this.

Are their respiratory DMEs that specialize in NMD care? Sure, those exist, but they are like rare unicorns hiding in obscure places. Too many individuals living with NMD and their families are being forced to self-advocate at every step towards getting the care they need which includes mechanical ventilation initiation and every phase of its use, including the process of moving from one brand of vent to another. Speaking up is critical for our survival; otherwise, we suffer, even die prematurely. More Lessons to Come? I don't consider my old-to-new vent transition fully complete. I anticipate more lessons to come, as my prescriber will be reviewing the settings selected for comfort and my usage data. Until then, I'm thankful for every night of good sleep on my new vent! It is my hope that others navigating this same process have a less challenging time than I did.

If you have any questions at all about our 20 Mile Walk Challenge, don’t hesitate to contact us. Unsure how to create a Facebook fundraiser for the challenge? We can coordinate a time to help you; just let us know. We will encourage and cheer you on during September in our private Facebook group, “20 Mile Walk Challenge.” We appreciate your support and look forward to working with you! By Andrea Klein Founder & President, Breathe with MD, Inc. I recently asked our Breathe with MD Support Group members for their tips for individuals living with Neuromuscular Disease (NMD) to adjust to bi-level non-invasive ventilation (BiPAP, BPAP, portable ventilator). Below are their thoughtful, experience-based tips. “Don't get discouraged. It takes time to get used to it, but in the long run, your body NEEDS the support for better sleep and less daytime fatigue.” - JC “Make sure your mask works for you! Size and style are very important. You always have options.” - LJ “My DME company gives me a two-week window to try a new mask without issue, and I love that they do that! If my mask style/size isn’t comfortable, I can change to something different in that two-week time, and then try the new mask for an additional two weeks. That’s something a new person should ask about, because a lot of times, people think they hate the machine when really they just hate their mask! I tried a smaller mask (or maybe nose pillows?! I can’t remember now, it’s been a while ago), that wouldn’t let me talk while I had had it on. Might not be a big deal to some, but I was totally freaked out! I HATED THAT. I’m so grateful I could switch, and now I have a mask that works great for me!“ - GL “Keep in contact with your respiratory therapist. A tincture of patience and a good working relationship may be required.” - SF “First, set the ramp time for as long as possible: 45 minutes is the longest I’ve seen. By the end of the 45 minutes, you’ll probably be asleep. Most insurances require at least 4 hours of usage each night, so set your alarm for 4 hours to meet their requirement. Do the 4 hours for 3 nights. On night 4 increase the time to 4 hours 15 minutes. Use that time for 3 nights. For night 7, increase the time to 4:30 for the next 3 nights. Keep increasing the time by 15 minutes every 3 nights until you get tired of waking yourself up to take off the mask and start sleeping through the whole night. Humidifier is your friend. IMO dry mouth is the biggest turn by off to using the equipment: waking up with a mouth so dry you can’t spit. Humidifier is a combination of tank temperature and how much humidity you want. It’s 2 separate settings on some machines. Getting used to a mask can be helped by wearing just the mask with no hose attached in the evening, before using it with everything connected.” -BY “My pulmonologist had me increase by an hour every few nights if possible. I found I needed two different masks due to my skin having some breakdown. Finding the right mask can be part of the challenge too so really take time with making sure no leaks and no pressure etc. I also found the bipap setting where it automatically turns on and off for you rather than you having to push the button on and off when connecting/disconnecting helps.” - LM “If you can’t tolerate the mask, try nasal pillows. Once I got the pillows, it was easy to tolerate. I’m up to 6 hours a night. That’s when my humidifier runs dry, and I wake up when my mouth dries out. I keep a water bottle by my bed.” - CD “If it feels wrong, it probably is. Make the call to respiratory for settings adjustments. Also, be aware that BiPAP isn't right for everyone and an active circuit ventilator setting may work better for you.” - KS “When I first got a bi-pap I only used it for a couple minutes during each day. Eventually, I worked my way up to being able to watch a movie during the day. Once you can handle having it on for a few hours then switch to only sleeping with it. I definitely wouldn’t try using it for the first time at night because it is a very weird feeling at first.” - KC “Most offices fit the mask while you are sitting upright. That’s totally wrong because your facial muscles sag when laying down. I found that when I asked to lay down to try on a mask and adjusted the straps laying down I got a better fit. RT at pulmo’s office had never heard of doing that. But now she does have the patients lay down to try a mask on and they do better when they use it that night.” - BY “Contact the doctor who prescribed it if things are off. For example, when I got my current BiPAP the amount of time for inhaling was just a second or less and the amount of exhale time was for many times longer. I need a longer inhale time than what the machine was set for. The machine wasn't giving me a second breath when I needed it as it was still on exhale mode. One phone call, and within an hour it was changed. The machine I have is set by the RT remotely, but only on doctor's orders. Keep telling you doctor or RT what isn't working so adjustments can be made. Expect it to feel weird at first. Learn to relax whilst using it during the day. Once the breathing cadence and mask are comfortable, work up to wearing it for one hour during the day. Then start using it at night.” - DD “If something's not OK, try to pin down what it is: 'Too fast,' 'Can't breathe out enough' for me meant the span (IPAP minus EPAP) was too low. 'My face is squashed” - get a different mask 'It's leaking in my eyes!!!' - lay a sock over your eyes and get a different mask. 'What does the problem feel like?'” - FP What tips do you have for someone getting adjusted to NIV? What worked for your successful adjustment?

Five Barriers to Starting Bi-level Mechanical Ventilation for Neuromuscular Breathing Weakness7/25/2023

By Andrea Klein Founder & President, Breathe with MD, Inc. It is vitally important to develop a working knowledge of breathing/respiratory muscle weakness and use that information to advocate (speak up) for appropriate care.  When an individual has a medical issue that can be managed, most of us assume it will be assessed and promptly managed. But that’s not always the case when the individual is living with a Neuromuscular Disease (NMD) and has respiratory involvement (breathing/respiratory and coughing muscle weakness). In this blog post, I’m covering five barriers to starting bi-level mechanical ventilation when the individual has an NMD and is experiencing underventilation during sleep. Delays in starting this method of moving air into and out of the lungs via BPAP, BiPAP, or portable ventilator for those with NMD can lead to an overall reduction in quality of life, respiratory infections, pneumonia, acute respiratory failure, and hospitalization. What are the barriers? 1. Lack of knowledge – If you don’t know what respiratory involvement is or that it’s possible in your form of NMD, you are unlikely to be familiar with symptoms or recognize that you need help breathing during sleep. Adults living with an NMD, increasingly those with late-onset and/or slowly progressive NMDs, are commonly uninformed about breathing and coughing muscle weakness and the options to manage these impairments. This lack of knowledge also occurs with parents of children and adolescents as well as adults who are newly diagnosed. No one should be ashamed of this as most have had many questions or were poorly informed at some point, myself included. It is vitally important to develop a working knowledge of breathing/respiratory muscle weakness and use that information to advocate (speak up) for appropriate care. The Breathe with MD, Inc. website is a good starting point for developing your own personal knowledge base to break down this barrier. 2. Denial – No one wants to admit that they have something wrong with a major life function like breathing. Symptoms are sometimes explained away as migraines, a need for more sleep due to the NMD disease process, anxiety, etc. Those who are highly successful in their career or with volunteer efforts and those who are busy with family are more likely to ignore the signs and symptoms they need help with their sleep breathing. All of our bodies have the amazing capacity to compensate for breathing muscle weakness, but we also have a threshold that once reached our bodies can no longer continue this compensation. That’s when a respiratory crisis occurs and that can prevent us from participating in decision-making. The Breathe with MD Support Group is an amazing way to navigate the denial barrier. A thorough, informed clinician who can answer questions and address your concerns can also successfully bring you through this barrier. 3. Fear – Few things are as alarming as having something wrong with your breathing. It is normal to be fearful of starting bi-level mechanical ventilation. Fear of allowing a machine to assist your breathing, fear of how that may feel, fear of a "new normal" all can keep you from moving forward in getting care and/or the necessary equipment. Communicating with peers who have experienced the same fears and have overcome them is comforting and can smooth the transition and adjustment phase for mechanical ventilation. Never underestimate the power of peer support to destroy fear and empower you! 4. Lack of access to appropriate care – When other barriers have been overcome, the next hurdle may be finding a clinician who has experience in evaluation and appropriate management of neuromuscular breathing/respiratory and cough weakness. Most clinicians list their expertise or special interest within their bio on the website of the medical institution or facility at which they practice. Sometimes, unknowingly, trusted and respected clinicians refer their patients to a clinician who is NOT experienced in neuromuscular breathing weakness. Unless the patient knows the common mistakes in the diagnosis and management of breathing/respiratory muscle weakness, they could be led to treatments that make them worse (i.e. CPAP and supplemental Oxygen alone, without mechanical ventilation) or make no improvement in their under ventilation. In some cases, clinicians wrongfully prescribe no intervention at all. For your awareness, “Based on CMS/National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidelines, there are four objective criteria that can be used to guide the initiation of noninvasive ventilation: (1) forced vital capacity < 50% of predicted (upright or supine), (2) maximal inspiratory pressure # 60 cm H2O or sniff nasal pressure < 40 cm H2O (upright or supine), (3) PaCO2 > 45 mm Hg, and (4) overnight nocturnal desaturation < 88% for 5 min. If a patient meets any of these criteria, it is appropriate to initiate noninvasive ventilation.9,59“ Reference: Bernardo J. Selim, Lisa Wolfe, John M. Coleman, Naresh A. Dewan, Initiation of Noninvasive Ventilation for Sleep Related Hypoventilation Disorders: Advanced Modes and Devices, Chest, Volume 153, Issue 1, 2018, Pages 251-265, ISSN 0012-3692, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chest.2017.06.036. The lack of access to physically reach a clinician with the needed experience is one of the most difficult barriers for someone with an NMD to overcome. Many areas within the United States (US) lack a clinician that understands the niche type of care that is needed for someone with neuromuscular breathing weakness. This could mean the individual might have to travel hours to reach a qualified clinician in their home state. Some drive or fly hundreds of miles for this multiple times a year. Not everyone with an NMD has the physical and/or financial means to travel outside of their immediate area, and they may have to settle for an inexperienced clinician with which they need to share information to get appropriate care. This does not come without challenges, because some cannot accept a patient having more knowledge than they do. This can result in the patient having to change clinicians multiple times until they find one that will partner with them to get appropriate care. Lack of physical access to appropriate NMD care overall is a global issue and tends to be worse in countries within Asia, Africa, and South America. Eliminating this barrier will not happen easily, but a starting point is for clinicians in these locations to be receptive to learning from rare disease patients who often are some of the most informed individuals experienced in gathering and sharing credible information such as peer-reviewed articles. The Breathe with MD, Inc. website can assist in this knowledge transfer as it includes downloadable PDFs and links to relevant medical articles. 5. Lack of access to mechanical ventilation devices – This barrier is less of a concern in the US where most are covered by private insurance, Medicare, and/or Medicaid. However, US medical insurance deductibles, co-pays, and non-capping monthly rentals can be too costly for individuals with NMD, leaving them to select less advanced, "rent-to-own" equipment that may not be best suited for their long-term needs. Programs for indigent individuals and financial hardship waivers exist and may reduce or eliminate the patient's mechanical ventilation cost. These programs may be operated by the respiratory care/Durable Medical Equipment (DME) provider or the respiratory equipment manufacturer. These are rarely if ever advertised, so the patient has to ask the DME if these options exist. It may be discouraging as one navigates through or around these barriers to access needed bi-level mechanical ventilation, but it is so worth it to experience improved quality of life and prolonged life with an NMD. What barriers did you experience along your journey to start bi-level mechanical ventilation? How did you overcome them? By Andrea Klein Founder & President, Breathe with MD, Inc. "Having this knowledge will assist in partnering with your care team, troubleshooting, medical self-advocacy (speaking up for yourself), and proactively managing your respiratory health." In this blog post, I’m covering seven Non-invasive Ventilation (NIV) settings-related topics everyone who uses NIV should understand if they are living with Neuromuscular Disease (NMD). Having this knowledge will assist in partnering with your care team, troubleshooting, medical self-advocacy (speaking up for yourself), and proactively managing your respiratory health. 1. Know your device type, brand, and model. “It’s black and gray, has a water container thingy, and is about the size of a shoebox.” No, that’s NOT the description I’m talking about. The following are some questions you should be able to answer about your home use mechanical/assisted ventilation device.

2. Know your machine. What I like to call a “basic bi-level” device (also known as a BPAP or BiPAP) is going to offer pressure-only support and fewer options to customize each delivered breath. This means it may not be synchronized with your breathing. It will have a lower maximum pressure setting which may not be high enough to support those with very weakened inspiratory muscles and usually will not have the ability to set the Expiratory Positive Airway Pressure (EPAP) lower than 4 cm H20. (Some with NMD need very low or no EPAP to achieve full breathing muscle rest during sleep.) The basic bi-level device will also have no internal battery and will not come with external batteries. You will be able to purchase external batteries, but in the United States (US), insurance often denies coverage of them. The cost of external batteries, how long the batteries can operate the machine, as well as a lack of a designed-for-use transport bag, will make this device less suited for use outside of the home. Basic bi-levels are considered “rent to own” in the US. Most medical insurance companies will require you to make 8-12 months of payments (depending on the specific insurance plan), and when the insurance plan’s "cap" is reached, nothing further will be owed. At that time, the patient will own it. Other alternatives include a non-portable ventilator (often unsupported by respiratory equipment providers) or a multi-mode, multi-prescription, portable ventilator that can be used for both non-invasive ventilation and invasive ventilation via a trach tube. Today's ventilators are larger and offer pressure, volume, and a combination of the two forms of support, with several different modes or types of ventilation available on the same machine. They offer more customization for each breath and may result in better synchronization between the user’s breathing and the device. Ventilators include internal batteries, external batteries, and in some cases “hot-swappable” batteries that can be removed and replaced during use, making them best suited for 24/7 users and those who will be taking their ventilation on the go. These devices can offer multiple prescriptions to be enabled for sleep, day use, and/or when more support is needed such as while ill, with a toggle functionality to move from one prescription to another. Portable ventilators tend to cost significantly more than the basic bi-level device and are not a “rent to own” option in the US but a continuous rental. Purchasing one of these “out of pocket” is generally not practical and makes their required regular maintenance and support difficult or impossible. A respiratory equipment provider is required to respond 24/7 to assist in supporting ventilators and replace them within hours or less time. If you owned the device yourself, you would be without access to a backup device unless you purchased a second one. Some who use ventilators have a spare in their home (often covered by medical insurance, if device use is at or near 24 hours/day). In other cases, the respiratory equipment provider keeps a device of the same make and model in their “fleet” so that a rapid replacement can occur, should your ventilator malfunction or for your use during required regular maintenance. 3. Know what mode of ventilation you are using and the settings enabled. You do not have to understand the way your settings work; that’s the Respiratory Therapist’s job. You, however, need to know what mode and settings are enabled on your mechanical ventilation device for a variety of reasons. You know the names of your prescription drugs and the prescribed dosages, so you need to know what your mechanical ventilation settings are. They too are a prescription written by your clinician. Store them in a note on your smartphone, in photos on your mobile device and/or computer, and/or print and keep them in a personal health binder, whatever works best and is the safest place for future reference.

The above are a few relevant questions, and the settings enabled on your device will depend on the mode of ventilation enabled. For example, a BiPAP S/T mode will not include a tidal volume. If you do not know what mode or type of ventilation is enabled and what the settings are, ask the prescriber and/or the respiratory care company that is supporting your device. This should have been provided with the paperwork you signed to acquire and get trained on the device. Like everything in your medical record, you have a right to receive it at any time. As those settings are changed, update your personal record of them. For years, I kept photos of my ventilator settings menu screens only on my smartphone. When I upgraded the phone, those photos inadvertently did not get transferred to the new phone. One afternoon, my Respiratory Therapist (RT) came to do a required software update on my portable ventilator. Later that night I realized my settings were no longer enabled; instead, what seemed to be default settings in an entirely different mode of ventilation were on the machine. (Both the RT and I should have tried the device before he left, and the subsequent problem would not have occurred. It was a lesson we both learned.) I called the respiratory equipment provider's after-hours support, and my RT came over promptly, but he was delayed due to difficulty in finding my settings in the paper chart and their not being in the electronic chart. It took a few weeks to catch, but a couple of changes we made in my settings a year or two before were not made when the settings were re-enabled during that emergency house call. 4. Understand active versus passive circuit. A well-known pioneer in mechanical ventilation is known for his use of active circuit ventilation with his patients. It requires that the ventilator tubing include an exhalation valve for the exhaled air (CO2) to enter and escape and that the mask interface has no holes for air to escape. Because most do include holes, the user is required to tape or glue them when using active circuit ventilation. Additional things to know:

A passive ventilator circuit is more commonly used today, as the majority of mask interfaces include holes for exhaled air (CO2) to escape. A basic bi-level device and a ventilator allow passive ventilation circuits to be enabled. 5. Know the common settings errors in Neuromuscular Disease (NMD). Ventilation settings can be problematic for those with NMD and often require weeks to get adjusted to them with multiple instances of the patient communicating with the provider and/or RT, asking questions, and sharing what feels wrong or uncomfortable. If you struggle with asking questions or requesting changes in what has been prescribed, this will be a more difficult process for you to get what is needed. Medical self-advocacy is an essential skill most living with an NMD develop during the initiation of mechanical ventilation if not previously acquired through other complex episodes of care. It seems, at least in the US, there is a lack of clinicians who understand the niche of NMD ventilation settings for restricted patterns of breathing and under-ventilation and an abundance of clinicians who understand CPAP settings for obstructive sleep apnea. The most common management error for those with NMD and weakened breathing muscles is for a clinician to prescribe CPAP (Continuous Positive Airway Pressure Support) with only one pressure to inhale and exhale against. Second to that mistake is for the clinician to prescribe bi-level ventilation with an EPAP that is too high for someone with weakened breathing muscles to exhale against. Generally, this number should be lower than 6, with some clinicians arguing it should be 4 or lower. Some schools of thought say it should even be set to 0, requiring active circuit ventilation. A third most common settings error is for the clinician to enable settings with low span. Span is the difference between IPAP and EPAP values. Some schools of thought say these numbers should have a difference of 10 or more, for example, 14 for IPAP and 4 for EPAP. It is not uncommon for someone to get their bi-level ventilation mode enabled with an IPAP of 12 and an EPAP of 8, and those settings will not assist in ventilating (moving air into and out of) the individual’s lungs during sleep, nor will they provide respiratory muscle rest, if the breathing muscles are weakened.

Part of why many have challenges getting settings enabled appropriately is that every person with NMD is different. The pressure, tidal volume, etc. that is needed for one person could be wrong for another. Factors like how much air one can hold in their lungs, their weight and height, whether their upper airway is subject to collapse during sleep, and how restricted their rib cage is from skeletal abnormalities that accompany NMD like scoliosis, kyphosis, etc. are all factors that can influence the settings enabled on their ventilation device. Sometimes an overnight sleep study will assist in this process but only if the clinicians present and reviewing the results from that study are familiar with neuromuscular breathing weakness and understand our weak effort to breathe is rooted in our muscle weakness. I wish I could say otherwise, but for many of us, it’s trial and error when it comes to mechanical ventilation settings, especially if we’re seeing a clinician who does not specialize in Neuromuscular breathing weakness. When we see a specialist in Neuromuscular breathing weakness, that clinician usually has the experience and knowledge to prescribe settings that are more appropriate and with fewer changes needed. For that reason, you may wish to obtain a second opinion referral to another clinician who can better assist with your settings. 6. Settings may need to change. The same way that our other muscle groups become weaker, in many forms of NMD, so do the breathing muscles. That means that the fully supportive, comfortable settings we may have worked hard to find could need to change over time. You may be wondering how you will know a change is needed. You could experience new fatigue and/or daytime sleepiness, require more hours of sleep to feel as rested as you did previously, and/or may develop new shortness of breath. Others that are monitoring their oxygen saturation during the day may find that after a certain time of day, their oxygen saturation drops consistently and does not improve with use of an insufflation exsufflation device/mechanical cough assistance. This could signal the need for a change in nighttime settings. Adjusting a setting (i.e. IPAP, tidal volume, etc.) may resolve the symptoms, but some may need to switch from one mode of ventilation to another (for example a move from BiPAP S/T to AVAPS S/T or AVAPS AE). Some individuals with NMD find they need to introduce some daytime ventilation or increase their hours of use with existing daytime ventilation. This could mean starting mouthpiece ventilation or using daytime nasal ventilation when one is not already doing so. This change in function is why many switch from a basic bi-level device to a multi-mode, portable ventilator, to have additional options and more flexibility as needs change. It is common to find that individuals with NMD quietly suffer and do not ask to explore mechanical ventilation settings changes or moves from one device to another unless they have a respiratory crisis or their clinician initiates the change. Settings changes usually require the coordination of both the device prescriber and the RT working with you to try different options. Most RTs work for companies that have rules that prevent their changing ventilation settings without a medical provider’s order to support the change. This is in part why your settings are checked at regular intervals and data feeds are taken. If a change is identified, you will need to answer for it, and your RT may feel uncomfortable working with you unless an order is in your chart to back up the change. Personally, I don’t make my own changes even though I have access to do so, in the event of an emergent need to change them, if no RT appointment were available, for example. What has helped to simplify my settings changes in the past is to contact both my neuromuscular breathing specialist and my RT about my concerns and any symptoms I am having. I’ve even recorded pulse oximetry during sleep with a device I purchased myself that allows reports to be generated to show drops in Oxygen saturation and have shared them with the neuromuscular breathing specialist. The doctor would then make a determination of which settings might be beneficial to change and faxes an order to the RT at the respiratory care company with a range of changes agreed to. For example, a suggestion may be made to change my target tidal volume with an increase of 10-30 points, whichever is most comfortable and relieves symptoms. For each potential setting change to consider, the doctor lists an agreeable range for the change, and the RT will come out and make only one setting change at a time, allowing me to try the change when made and for a few days up to two weeks. Once a final selection of any one setting change is made, the RT and I will determine if we want to introduce another change the physician has authorized. We never change more than one setting at the same time, because if we see improvement, we won’t know which setting change made the difference or if it was both. For me, the settings change process requires the RT to come to my house multiple times, and when final selections of settings are made, the RT faxes back the physician with those details. Then the physician writes and faxes the RT a new order without the ranges and just the specific values. The updated order is filed in my chart with the respiratory equipment provider. 7. Everyone is different; there is no one right collection of settings. Periodically, someone will ask for Breathe with MD Support Group members’ settings to be shared. I have participated in this exercise, sharing my own settings. But we are all so different and no two people of the same size, pulmonary function test results, and form of NMD are going to use the exact or even similar settings. It may be helpful to compare settings to determine if one’s settings may be completely off base, but a wide range of settings comparisons can leave the questioner more confused. The bottom line: mechanical ventilation settings are complicated, and no one approach to determining the best settings works for everyone. Having at least basic knowledge should help you be better equipped to advocate for your care needs until the correct settings are enabled for your optimal support and comfort. Keep in mind that there is typically an adjustment phase for even appropriate settings and that some temporary soreness may be experienced in breathing muscles that are getting stretched more than they're used to. For any questions, reach out to your prescribing clinician and/or RT. Editor's Note: Are you an individual living with a Neuromuscular Disease (NMD) who uses mechanical ventilation and have a story to share about hospitalization, illness, emergencies, advanced medical testing (MRI, CT scan, etc.), or surgical procedures? Or, do you have another idea for a blog post? Start the process of helping others in the NMD community by telling us about it at https://breathewithmd.org/storyform.html, or send an email to [email protected]. Did you know that the public charity, Breathe with MD, Inc., which sponsors this blog, offers #LivingVentilated shirts?! For the simple, two-sided #LivingVentilated shirt, just go to https://www.bonfire.com/livingventilated/ to select from nine different style offerings: Premium Unisex Tee, Women's Slim Fit Tee, Classic Tie Dye Tee, Classic Long Sleeve Tee, 3/4 Sleeve Baseball Tee, Pullover Hoodie, Tie Dye Pullover Hoodie, Tie Dye Crewneck Sweatshirt, and Women's Tie Dye Cropped Hoodie. The back of the shirt features the Breathe with MD, Inc. logo. Each style features different colors, so there is something for everyone. Our new, two-sided "Peace, Love, and #LivingVentilated" Shirt design is a must-have for your wardrobe! Get it at https://www.bonfire.com/peace-love-and-livingventilated-shirt/. The back of the shirt features the Breathe with MD, Inc. logo, and the shirt is available in four different styles: Classic Tie Dye Tee, Tie Dye Crewneck Sweatshirt, Tie Dye Pullover Hoodie, and Women's Tie Dye Cropped Hoodie. Each style features different colors, so again, there are many options. Let the world know you're #LivingVentilated, and order your shirt today! To see all items in the Breathe with MD,Inc. Charity Boutique, go to https://www.bonfire.com/store/breathe-with-md-inc/. It's not too soon to be thinking about gifts for fall and winter birthdays and the holidays. Get your shopping done early and before the shipping rush! Our order batch is closing on September 14, so don't wait too long. All proceeds go to support the mission and programs of Breathe with MD, Inc. We appreciate your support.

By Andrea Klein Founder & President, Breathe with MD, Inc. "I genuinely believe they are all well-meaning and subscribe to the belief that we learn about and accept differences through questioning."  I’ve been using mechanical ventilation for breathing muscle weakness since December 2013, first as a basic BiPAP S/T with a backup rate. Then in July 2015, I transitioned to a multi-mode portable home use ventilator with AVAPS AE for night use and MPV (mouthpiece ventilation) for daytime use, as needed. I have many friends who also live with a Neuromuscular Disease (NMD) that have used a form of mechanical ventilation for much longer, some as much as 25-30 years. People can ask and say some unexpected things about mechanical ventilation. I genuinely believe they are all well-meaning and subscribe to the belief that we learn about and accept differences through questioning. For that reason, I don’t mind as this is an opportunity for me to educate those individuals. I hope that’s what this post does, teaches you something you didn’t know before reading it. Below is what people have said to me about mechanical ventilation and a summary of what my responses have been. 1. “Why not just use oxygen?” The primary issue when a Neuromuscular Disease (NMD) has weakened the muscles used to breathe and cough is that it becomes more difficult for air to move into and out of the lungs, a process called ventilation. When we fully support the process of moving air into and out of the lungs through mechanical ventilation, we prevent or resolve any oxygenation issues. Oxygen does not help move air into and out of the lungs and can actually create problems for those with weakened breathing muscles. Unventilated supplemental oxygen (used through a nasal cannula and without mechanical ventilation) led to my middle sister Cheryl’s death and is one of the most common inappropriate interventions for neuromuscular breathing weakness. You can learn more about the dangers of unventilated supplemental oxygen in this short video that I made, and be sure to visit the Oxygen Caution page of the Breathe with MD, Inc. website at https://breathewithmd.org/oxygen-caution.html. 2. “I wish I could sleep that much!” Getting adequate sleep is critical for health, but it’s even more important for those with weakened breathing muscles. When we use mechanical ventilation during sleep with adequate settings enabled, the bi-level respiratory device reduces or eliminates our effort to breathe during sleep so that we may achieve “breathing muscle rest.” The amount of time we need to sleep on our mechanical ventilation to achieve the ability to be alert, productive, and to remain off of our mechanical ventilation during the day varies from person to person. Any illness or symptom that arises overnight and interferes with sleep amount or quality can result in the need to prolong that sleep. Another factor is that many of us have a tendency to “overdo it” because our weakened limb muscles wear out before our drive for doing things does, often before we have realized our own limit. And that limit can vary from day to day and be influenced by many factors. Often, it’s not until the next day that we realize how worn out we are. The way we typically recover from this is to sleep more. Many of us also take longer to recover from illness, especially those of a respiratory nature, and that too means we may need to sleep more. 3. “I couldn’t do it; you are so brave!” Most of us that use mechanical ventilation for neuromuscular breathing weakness know we must use it to maintain our quality of life and/or prolong our life. Respiratory failure is the most common cause of death for someone living with an NMD, and many of us have seen this happen to our friends and loved ones, so we aren’t being brave. We are simply doing what we have to do to survive and thrive. 4. “I use CPAP too.” Ugh! This one gets old explaining. CPAP (one continuous positive airway pressure) and bi-level mechanical ventilation (two different levels of positive airway pressure, one for inhaling and another reduced one for exhaling) are not the same. CPAP can be harmful to those who live with an NMD and have weakened breathing muscles and does not assist in moving air into and out of the lungs. For a more detailed explanation, please watch my short video. 5. “Have you thought about getting an Inspire implant?” The Inspire implant is for individuals with obstructive sleep apnea. Those who live with neuromuscular breathing weakness may have sleep apnea, but typically that’s a misdiagnosis as the sleep study equipment and/or the reader of that study interprets their shallow, weak breathing effort as stopping to breathe (apnea) instead of simply a weak effort to breathe. Neuromuscular breathing weakness is not an obstruction; it’s a restrictive condition. Even if the individual living with an NMD has sleep apnea too, they would still need bi-level mechanical ventilation to ventilate their lungs, and this implant does not do that. 6. “Try inhaling essential oils, and you’ll breathe better!” There is no way that inhaling essential oils will make weakened breathing muscles suddenly work better. Anyone who tries to convince you of that is running a scam. 7. “Will you eventually need a lung transplant?” In neuromuscular breathing weakness, the primary issue is not with the lungs; the issue is with the muscles that move air into and out of the lungs, so a transplant would be pointless and not help. 8. “I was on a ventilator after my accident; it was awful!” I am sure that using a ventilator in the ICU or hospital via endotracheal intubation is frightening, especially for someone who has never experienced having a piece of equipment move air into and out of their lungs. In contrast, for someone with neuromuscular breathing weakness who connects their home use ventilator to a nasal, oronasal, full face, or nasal pillows mask, or a tracheostomy tube, we generally love our ventilators. They keep us alive and able to do what we need and want to do in and outside of the home. 9. “When I get to that stage, I just want to die.” This comment is a painful one for me to hear from someone who is living with an NMD because I know that whatever preconceived notion they have about mechanical ventilation is likely based on a lack of knowledge and/or inaccurate information. When someone is alive and able to be proactive about their care outside of a crisis, making a choice to simply die seems like they are needlessly giving up. I respect their right to make that decision, but I still do not like or agree with it. I believe we are all alive for a purpose, and that purpose does not end when we need mechanical ventilation. 10. “You’re going to get dependent on that and eventually be unable to breathe on your own.” My response to this is, “So what if I do?” If I need something to breathe in order to have quality of life and to prolong my life, I need it, so it isn’t going to matter if using it makes me eventually need it more. I’ve been using mechanical ventilation for just over eight and a half years, and the amount I currently need it each day versus when I started using it has not increased by more than two to three hours per day on average. This is going to vary from person to person, but we cannot allow fears of needing something more over time to prevent us from using it. Those are the 10 unexpected things people have said to me about mechanical ventilation. What unexpected things have people said to you? I would love to know. Editor's Note:

Are you an individual living with a Neuromuscular Disease (NMD) who uses mechanical ventilation and have a story to share about hospitalization, illness, emergencies, advanced medical testing (MRI, CT scan, etc.), or surgical procedures? Or, do you have another idea for a blog post? Start the process of helping others in the NMD community by telling us about it at https://breathewithmd.org/storyform.html, or send an email to [email protected]. By Andrea KleinFounder & President, Breathe with MD, Inc. “I had a lot of anxiety about it since the beginning of the pandemic, because I didn’t know how my body would react.” --- Nora Ramirez  Individuals living with Neuromuscular Disease (NMD) have varying degrees of anxiety about what would happen if they contract COVID-19. The concern has shaped our behavior and limited our activities for more than 22 months. Nora Ramirez, who lives in California with Facioscapulohumeral Muscular Dystrophy, (FSHD) and uses mechanical ventilation said, “I had a lot of anxiety about it since the beginning of the pandemic, because I didn’t know how my body would react.” The fact that Nora was hospitalized with three prior episodes of pneumonia made her even more concerned. In late November, she had to be tested for COVID-19. We talked about her experience and knew sharing it would help others with an NMD. It was the Sunday before Thanksgiving, and Nora developed a dry, itchy throat that made her want to cough. The next day, she was coughing a little more frequently, but it was a mild, dry cough without throat pain. By Tuesday, she was coughing more, so she got tested and expected to have results in two to three days. No pharmacies in her small town had same-day appointments for rapid tests. “By Wednesday morning, when I woke up,” Nora explained, “I didn’t feel good at all.” She had a lot more dry coughing with an additional symptom: her chest felt like someone was hugging it too tightly. This is something she’s experienced with pneumonia. She also struggled to get out of bed. Normally, Nora can independently use the restroom without difficulty. But that day she said, “Just going to the restroom was very exhausting to me. Around 3:00 or 3:30 p.m., I decided I needed to go to the hospital.” She went to the ER but didn’t think it would be COVID-19, because she was not running a fever and had not lost her sense of taste. Along with a blood draw to test for several things, clinicians tested her for COVID. She was positive, and the result of her previous test was still unknown. As Nora talked to the clinicians, she had to stop to take a breath every six to seven words. “My average normal resting heartrate was usually in the seventies,” she said, “and at times it was reaching 140.” Clinicians wheeled her on the stretcher into the imaging department for a chest x-ray and a CT scan with IV injected contrast to check for pneumonia and blood clots in the lung. “The doctor did inform me that the two major concerns from COVID were getting pneumonia or a blood clot in the lungs.” Her chest was clear, and she had no clots; but Nora described being exhausted just from breathing. While lying down, her heart rate would drop to a still very high 120 to 130 beats per minute. The doctor recommended a monoclonal antibodies treatment which involved a series of four injections, two on each arm, near her armpit, and one on either side of her belly button. Nora explained they were painful but not unbearable and that the skill of the nurse may have factored into this. “The injection was given sideways,” she described, and “liquid formed a little pouch or bubble under the skin.” It “absorbed fairly quickly,” and even with the discomfort, she did not regret getting the treatment. Nora stayed in the ER for five to six hours, also receiving IV fluids and potassium pills to address the low potassium caused by COVID. Her symptoms did not worsen much more, but she did experience what the doctor advised, that “COVID-19 symptoms get better and then worse on day 6 or 7.” “They did not get severely worse,” she shared, “I just had a little more coughing and sleepiness or tiredness around those days.” The doctor explained she would need to return to the ER, if she could not speak more than three or four words without taking a breath. Most symptoms, including a runny nose, left after a week. But the fatigue and increase in heart rate, triggered by sitting upright and getting out of bed, persisted. She joined an FSHD group on Facebook and asked if anyone knew how to “lighten the load on her heart.” Their suggestions were to use her BiPAP (bi-level mechanical ventilation) during the day or as much as possible, even though prior to COVID, she normally only used it for sleep. This immediately reduced her heart rate to 100. She used her mechanical ventilation all the time, except for when she was using the restroom or eating. Even after this period of bedrest, when Nora and I talked on December 26, she was still experiencing tiredness that was unlike her usual FSHD related fatigue. “I went to the doctor just a few days ago, and it felt very exhausting to walk to the main lobby.” she said. Nora explained that her legs seem to be weaker and tire more easily now. If she gets up too quickly, “It’s like my legs just give out, like they turn to noodles, and this had never happened before.” She feels as if her knees are wobbly or not secure, something her mother experienced after she too recovered from COVID-19 at a different time. The doctor told her it could be the bedrest or "the way COVID took a toll on her body" and that she’s still recovering from it. He said that some can have these feelings of exhaustion for months beyond their illness. Nora shared with me, “Last weekend, I did go to the ER again. I pushed it maybe a little too far, because I was walking a lot the day before.” She woke up nauseated, was blacking out, experiencing chest tightness, and thought maybe these were heart related symptoms. It turned out she was okay but did have to stay in the ER for eight to 10 hours. They did an Electrocardiogram (EKG), chest x-rays, a lot of blood work, and an Arterial Blood Gas (ABG) that measures Oxygen and Carbon Dioxide levels in the blood as well as the body’s acid-base (pH) level. I asked Nora if at any point during either ER visit whether clinicians tried to administer supplemental Oxygen. (To learn more about the potential dangers of unventilated supplemental Oxygen for an individual with an NMD who has weakened breathing muscles, please see https://breathewithmd.org/oxygen-caution.html.) The first ER had her prior medical records and did not try this. The second hospital’s ER did not have her medical history but administered nothing, not even IV fluids. Nora told clinicians she should not be given Oxygen, that she uses a BiPAP, and she recommended they do the ABG test. (She had recently reviewed the Breathe with MD, Inc. website, joined the Breathe with MD Support Group, and learned from group members that others with an NMD had suffered when supplemental Oxygen was used without ventilation assistance.) In her second ER visit, clinicians refused to place Nora on bi-level ventilation after she left her own BiPAP at home in the rush to get there. She said, “I feel they really did not understand Muscular Dystrophy. They said if my Oxygen levels were good, I didn’t need my BiPAP. I tried to explain it in several ways, but they kept referring to my Oxygen levels being perfect. The doctor sent in a respiratory therapist, and she too said ‘no’ to the idea of a hospital BiPAP.” They treated Nora as if she didn’t know anything, “Like I was loopy or something.” They also did not agree with her method of staying conscious during her fainting episodes. A doctor had taught her as a child that when ammonia (an ingredient in smelling salts), is not available, sniffing rubbing alcohol or distilled vinegar would keep her from fainting. “I didn’t know what would happen if I blacked out,” Nora shared, “so I kept sniffing it [rubbing alcohol] every time I saw black, losing consciousness. I got a lot of negative comments from the nurses there.” They did not understand why she was using it, and one nurse questioned if she was drinking the rubbing alcohol. This second ER experience required Nora to speak up for herself, and it was stressful navigating symptoms along with concerns that clinicians would not provide the right care. She was discharged home without clear answers for the cause of her symptoms and is continuing to heal. Below is a list of things Nora shared that may or may not have influenced her recovery. Check with your medical provider about any home treatments, vitamins, supplements, or prescription medications that may be best during any illness.

Editor's Note:

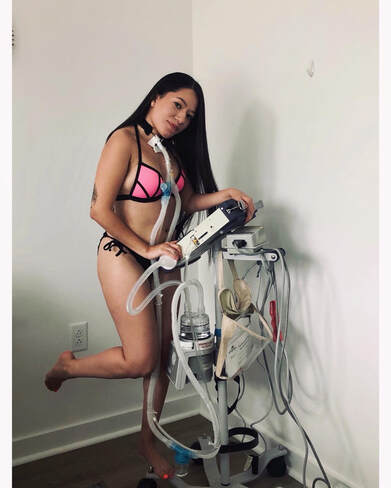

Are you an individual living with a Neuromuscular Disease (NMD) who uses mechanical ventilation and have a story to share about hospitalization, illness, emergencies, advanced medical testing (MRI, CT scan, etc.), or surgical procedures? Start the process of helping others in the NMD community by telling us about it at https://breathewithmd.org/storyform.html, or send an email to [email protected]. If your story is selected, we can assist by interviewing you and writing your "Living Ventilated" blog post. "I’ve accepted and grieved the things I cannot do and focus on the things I can do. It’s so important to take things one day or even one hour at a time."  Hola. I’m Stephanie Chicas, I am 28 years old, an art/wine/dance fitness/and taco lover with a disability and chronic illness. At age 13, I was diagnosed with Congenital Muscular Dystrophy (SEPN1 mutation). I use assisted ventilation via tracheostomy while I sleep and sometimes during the day. I went 13 years experiencing shortness of breath, migraines, muscle pain, weight loss, and falls with no diagnosis. It wasn’t until I woke up one morning with vertigo and extreme shortness of breath that I underwent various tests and follow up by doctors. My life completely changed after that morning. I was hospitalized for two months with what we thought would be one week of recovering from pneumonia. Within that first month of being hospitalized, I was heavily sedated and intubated and could not regain the strength to breathe on my own. Three weeks into my hospital admission, a tracheotomy was performed, and this is when my journey with a trach and ventilator began. Before the tracheotomy surgery, I had no knowledge of a trach or mechanical ventilators. The child life specialists were the ones to educate and help me feel comfortable with the operation, care, and medical equipment. I remember being shown a picture of Catherine Zeta-Jones who had a trach and having a doll made for me with the IV’s, NG tube, and trach tube. The way the child life specialist addressed my concerns and normalized my experience helped me cope with this new experience. And while it took me years to learn and perform my own respiratory care, it feels empowering to do so. So now, I change my own trach, suction myself, administer treatments, change the ventilator’s tubing, and have even managed to wean myself off the ventilator. I went from 24/7 ventilator use to now needing it to sleep or when fatigued. While the doctor said I’d be ventilated 24/7 for the rest of my life, I chose the path that was right for me. The sudden onset of illness, tests, and surgeries was traumatizing. If it wasn’t for my support system and child life specialists, I would not have been able to have the motivation and resilience to face everything. My life has been impacted in many ways. There’s good and there’s bad. Both valid and true. Accepting the diagnosis and how it has affected me has helped me cope on this roller coaster of a journey. On the physical side, my body has always been fighting with Muscular Dystrophy (MD), but it wasn’t until I was nearly 13 that on-going testing was done. It took a medical trauma for me to get the help I had deserved all along. We can imagine what 13 years of symptoms and gaslighting can do to someone. For me, it has caused anxiety. Along with anxiety though, there’s also the confidence. And I don’t say this to disregard the emotional toll MD has had on me but to accept both truths. Because while I do become anxious in social settings where I think of accessibility, energy consumption, germ exposure, what symptoms will come and if they’ll be manageable, I have also gained a lot of confidence from this. My confidence has gradually grown over the years and felt more ingrained within me when I felt comfortable learning about and sharing my disability and chronic illness. My ability to speak up, have courage, and be more authentic has increased a lot since diagnosis. We all have our struggles and our own capacity to handle certain experiences. Dealing with a disability and chronic illness is anything but easy. Being disabled and chronically ill for me feels like being a 24/7 nurse, receptionist, counselor, social worker, and care manager. Over the past fifteen years, I’ve gained knowledge in medicine, organizing, managing nursing schedules, knowing how to work with health insurance, etc. It all can get overwhelming, but with therapy, hobbies, and my support system, the journey of being disabled and chronically ill feels easier. It took me 10 years to finish my associate’s degree, but I did it. I have difficulty doing dance fitness, but I do it when/how I can. Volunteering to foster animals and attending charity events was tiring at times, and yet again I did it. Being vulnerable and sharing my journey is honestly still uncomfortable at times, but I still do it. All these things I do, with moderation, because it’s what brings me joy and growth. I’ve accepted and grieved the things I cannot do and focus on the things I can do. It’s so important to take things one day or even one hour at a time. Disability and chronic illness look different on everyone, and we all unfortunately do not have equal access to the care we deserve. I carefully decide what I can handle, face setbacks, and have had to fight for my care. So, my advice to someone living with an Neuromuscular Disease (NMD) is to go at your own pace and continue your fight. “The most beautiful people we have known are those who have known defeat, known suffering, known struggle, known loss, and have found their way out of the depths. These persons have an appreciation, a sensitivity, and an understanding of life that fills them with compassion, gentleness, and a deep loving concern. Beautiful people do not just happen.” --- Elizabeth Kubler-Ross Editor's Note:

So, what is your story? Start the process of telling us at https://breathewithmd.org/storyform.html or send an email to [email protected]. |

AboutLiving Ventilated celebrates those in the NMD community who use assisted ventilation. Archives

August 2024

Categories |

Breathe with MD, Inc. is a U.S. registered 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization. Donations are tax deductible to the extent allowable by law.

Note: This website should not be used as a substitute for medical care. For medical care or advice, please seek the care of a clinician who specializes in the breathing issues of those with Neuromuscular Disease (NMD).

Web Hosting by Hostgator

Note: This website should not be used as a substitute for medical care. For medical care or advice, please seek the care of a clinician who specializes in the breathing issues of those with Neuromuscular Disease (NMD).

Web Hosting by Hostgator

RSS Feed

RSS Feed